Higher EU climate targets: What does this mean for Austria?

Published:

I published a blog post in the Austrian newspaper die Presse giving an overview of the (then) current debate in the EU Parliament and Commission regarding changing the 2030 emission reduction targets. As part of a project for an Austrian government ministry, we created a tool which would determine a carbon emission budget for the EU depending on input assumptions, and then allocate that budget to EU countries depending on different equity considerations.

The original article found here is in german, but an english translation can be found below!

Ramping up EU climate goals: Implications for Austria

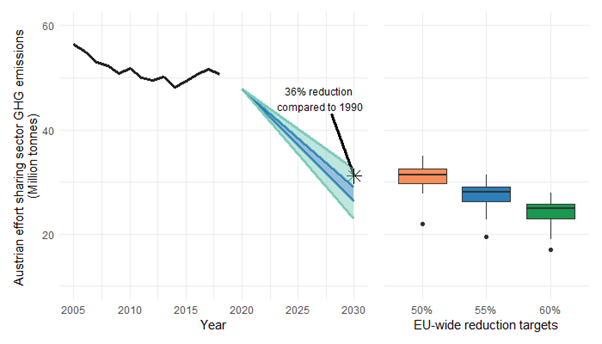

Amidst the chaotic landscape of 2020, the EU has been re-examining its near-term climate plans. The European Commission has suggested that the current target for 2030 of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 40% relative to 1990 levels, needs strengthening, and has suggested a 55% reduction [1]. In late October, the European Parliament voted to recommend a more ambitious 60% reduction [2]. In the end, the target will be decided upon by the Council of Ministers over the coming year. What could this mean for Austria, and how much could the Austrian 2030 target – currently a 36% reduction compared to 1990 levels – increase?

Part of the answer is easy, as part of these reductions will come via changes in the number of allowances distributed through the Emissions Trading System (ETS). However, for other all other areas of society not involved in the ETS (everything outside of power stations and large industrial plants) countries will have individual reduction goals. Dividing this remainder of allowable emissions is less straightforward. A basic approach would be to equally divide future emissions over the next 10 years based on population (known as an equal-per-capita or EPC approach). Alternatively, countries could be allowed to start from their current level of emissions and reduce to some lower common amount in the future (known as contraction and convergence or CAC).

But these two approaches to sharing the effort of climate change mitigation are overly simple and could be seen as unfair, mainly because they do not take into consideration any aspects of the past, nor do they account for the different abilities of member states to reduce their emissions. As an example, we can think of emissions which have occurred prior to 2020. Neither distribution approach considers the possibility that certain countries may have emitted much more than others. Worse still, a CAC approach gives more emissions to high emitters over the transition period.

As emissions will be limited, it may be preferrable to prioritize how they are used, for instance giving preference to activities which increase human well-being. It can also be argued that countries’ ability to reduce emissions should be considered. This is already the case today; the 40% EU-wide reduction is distributed among countries weighted by national GDP per person to avoid overly burdensome reductions in countries less able to easily reduce as compared to others.

Coming negotiations will likely address such arguments when deciding upon distribution of 2030 emission targets. In a recent brief, researchers from the University of Graz, the Austrian Institute of Economic Research, and the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis [3] have tried to determine the possible ways such considerations could be taken up, and how resulting distributions might look for EU countries.

Their work identifies five ways that a basic approach like EPC or CAC can be qualified to consider such aspects. In discussions on the future climate goals, the following arguments could be taken into consideration, using modified distribution mechanisms:

- Ability to reduce emissions: Countries are not equally able to reduce their impacts over the next decade and as such, those states which can more easily reduce their emissions should do so to a larger extent.

- Avoiding poverty: Emissions-intensive activities have been linked with increasing standards of living. As we phase out these activities, the remaining emissions we have should be used to further enhance people’s livelihoods and increase well-being. Thus, emissions should be prioritized for those countries with the highest levels of poverty.

- Increasing use of renewable energy sources: Countries which in the past have increased their use of green energy and increased energy efficiency have likely improved well-being for others in the EU, and should be rewarded to some degree and see increased benefits for their early decision to ‘go green’.

- Considering historical emissions: To address the large failing of basic distribution mechanisms, past emissions can be incorporated, and distributions weighted based on the over(or under)emission of GHGs compared to other EU states. In this case, historical emissions are seen as occurring since 1995, when the second IPCC Assessment Report was published, and could be considered a point in which there was broad agreement that climate change is a human-caused problem.

- Benefits from emissions before 1995: Many emissions caused prior to 1995 were the result of construction of infrastructure such as roads, public buildings, electricity distribution networks, and so on. People still today benefit from such projects and their associated emissions, and as such they should be considered. This would allow for countries where such development did not occur to have an increased emission budget and to reap similar benefits.

Considering these aspects when distributing the emissions allowed within the EU under a 50, 55, or 60% reduction target can result in a wide range of results for individual member states. The figure above illustrates just how wide the range of possible results may be for Austria. Under a 55% scenario, Austrian emissions (outside of the ETS) in 2030 could likely range between 32 million tons to just above 19 million tons, a difference of around 65 million tons over the ten year period, more than one year’s worth of non-ETS emissions.

The decision of how to distribute emissions reductions could take into account all or some of the above qualifications in various combinations, and recognition by the Council of such aspects could lead to drastically different burdens as compared to the previous goals. While we will have to wait for the final decision after rounds of negotiation, Austria – and the rest of the EU – would do well to prepare for the possibility of drastically increased emissions targets over the next decade.

[1] European Commission, Amended proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL establishing the framework for achieving climate neutrality and amending Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 (European Climate Law), vol. 2020/0036 (COD). 2020.

[2] European Parliament, Amendments adopted by the European Parliament on 8 October 2020 on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing the framework for achieving climate neutrality and amending Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 (European Climate Law). 2020.

[3] K. W. Steininger, L. H. Meyer, S. Schleicher, K. Riahi, K. Williges, and F. Maczek, “Effort Sharing among EU Member States: Green Deal Emission Reduction Targets for 2030,” Wegener Center Verlag, Graz, Austria, Research Brief 2–2020, Oct. 2020. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.25364/23.2020.2.